Beyond Fabergé: The great Russian jewelers

{module Ads Elite (xx)}

Fabergé was not the only master craftsman and jeweller in Imperial Russia. Other talented artisans created enamelwork and samovars for the wealthy. The 19th century produced many talented jewellers in Russia.

The whole world has heard of jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé, purveyor to the imperial court of Russia and the creator of the celebrated Fabergé eggs, yet the 19th century produced many other talented jewellers in Russia. Although they are not household names, their works are no less valuable. Until the mid-19th century, jewellers in Russia were considered to be ordinary craftsmen. It was only when they began to take part in international exhibitions that their names turned into commercial brands.

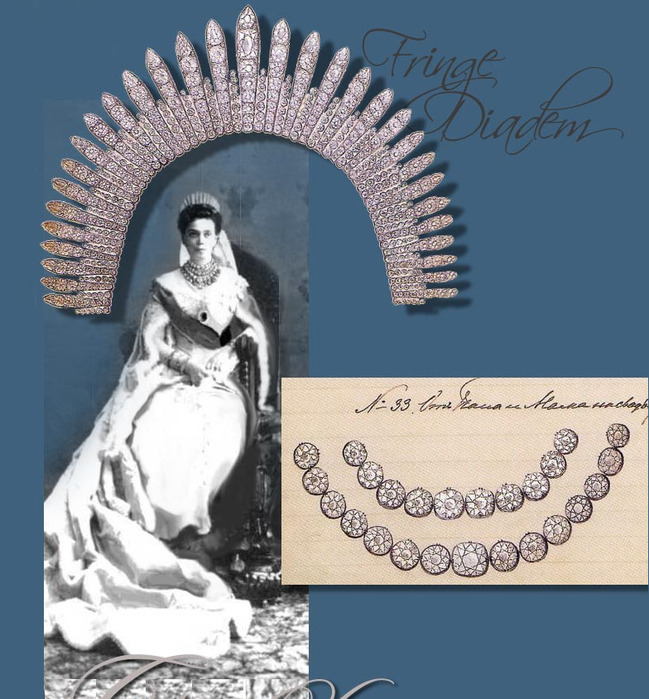

The Bolins, a family of Swedish jewellers,

first came to Russia in the early 19th century, several decades before Fabergé. In total, they served six Russian emperors – no easy task. Among other duties, their main assignment was to design and make trousseaux, or bridal outfi ts, for tsars’ daughters. A wedding set alone could cost as much as a house in the centre of St Petersburg. It usually consisted of a wedding crown, several diadems, a necklace, and bracelets. Complementing these treasures were also rings and earrings. On the eve of a wedding, the princess’ new jewels were displayed for everyone to see. That was an old custom, as the value of a bride was determined by how much her trousseau had cost.

The House of Bolin operated in Russia until World War I. At its outbreak, the then-owner of the firm, Wilhelm Bolin, happened to be in Germany. He tried to return to Russia via Sweden but could not go further than Stockholm, where he subsequently opened a store and soon began to work for the royal family of Sweden.

The jewellery workshop of merchant Pavel Sazikov dates back to 1793. His son Ignaty brought to the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London a collection of works inspired by traditional peasant life. The items on display featured a bear with its tamer, a milkmaid, a candelabrum commemorating the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, and other works inspired by folk themes. The candelabrum received a silver medal at the exhibition, and Ignaty returned to Russia a famous man.

At the Vienna Exhibition in 1873, jeweller Ivan Khlebnikov created a sensation with his samovar and tea set. The samovar stood on rooster feet and had handles in the form of rooster heads, while the cups in the tea set were decorated with precious stones and enamel. It was an object of unusual beauty that could not but attract interest and admiration. Khlebnikov returned from the exhibition proud as a cockerel and threw himself into his work with renewed energy. He took his themes from history and literature: scenes from the lives of Tsar Ivan the Terrible and Russian Orthodox Church saint Sergius of Radonezh, or the poems of Mikhail Lermontov. The most interesting of Khlebnikov’s works are his enamels. The State Historical Museum in Moscow has a wine set consisting of a carafe in the form of a rooster and cups in the form of chickens decorated with champlevé enamelling. He also made silver and gold dishes using the same technique.

Enamel was the trademark technique of another outstanding Russian jeweller, Pavel Ovchinnikov.

He was famed for his fi ligree, painted and stained-glass enamels. Filigree enamel used to be popular in Kievan Rus, where it had fi rst been brought from Byzantium, but the technique was lost during the years of the Mongol invasion of Russia. It was Ovchinnikov who revived that lost craft. His was an unusual life story. Born a serf, he displayed a talent for drawing at a very young age and was sent to become an apprentice to a gold- and silversmith. After eight years of toil, he managed to save enough money to buy his freedom. He subsequently married and opened a workshop of his own. By the time Ovchinnikov was just 24, he had an annual turnover of half a million rubles and he employed 600 people. By the age of 35, Ovchinnikov had become a purveyor to the Imperial Court and an honorary citizen, and had been decorated with several state awards.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, jewellers began to leave Russia. They found it impossible to work in a country blighted by hunger and desolation, where jewellery was being expropriated for the needs of the working class. The craft of the jeweller was later revived, albeit by a different school and with a different aesthetic.

{ (jewel)}